When: Thursday October 10, 2013 7:00-9:00PM

Where: New Art Center, 61 Washington Park, Newtonville, MA

How: Official Website

Cost: FREE.

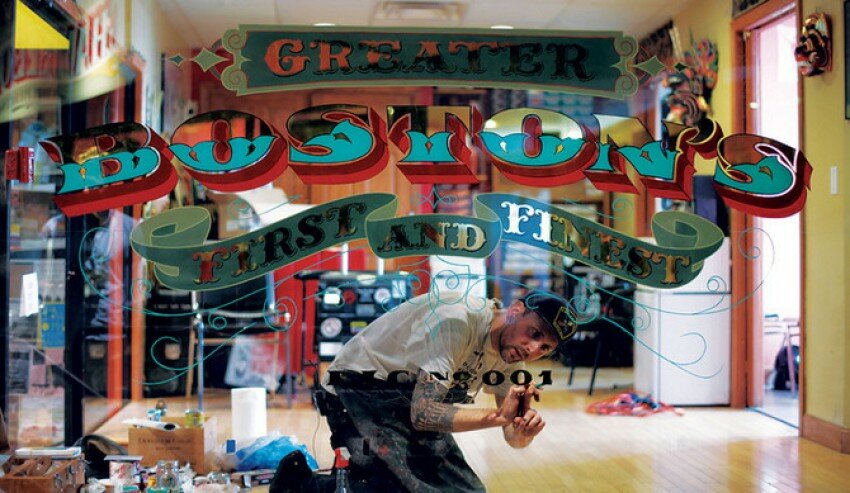

What/Why: “As a part of the Pedigree exhibition at the New Art Center, Josh Luke and Meredith Kasabian of Best Dressed Signs will lead attendees through a discussion exploring the history of sign painting, applications and misconceptions of the craft, and its relevance today. The talk will coincide with a demonstration of gold leafing, a complex sign painting technique that is the cornerstone of the duo’s installations.”

——-

Next Thursday. Be there.

The duo has been hard at work preparing intriguing research about the history of gold leafing, traditional signage, and the secret lives of gilders to share with you.

As an amuse-bouche, I have included a talk Meredith recently gave at the ICA during the Barry McGee retrospective entitled, “A History of Signs and how we and Barry McGee make Space into Place” after the jump.

Settle in and enjoy!

———————-

I’m originally from Boston—born and raised—but I lived in San Francisco for twelve years and Barry McGee’s art was part of my daily existence there for the whole expanse of my 20s. His art and graffiti are everywhere on the streets of San Francisco and the more I’ve been looking at his work lately, the more I’m realizing what an important role his art played in my time there. As I look at his work now, three years after I’ve moved back to Boston, I’m brought back to that specific time and place in my own life and it’s occurred to me the extent to which my life has been shaped by forces other than my own. Everyone’s life is shaped at least in part by their surroundings—by the places that they live with and traverse every day. These places that mean so much—that mean home—are important because they’re made by people. And not just by city planners and architects and graffiti writers and public artists, but by regular people who make meaning out of their city space simply by living in it.

Before I go on, I just want to define some of my terms, specifically the difference between the words “place” and “space” because they’re not interchangeable in the way I’ll be discussing them. Space can be defined as something abstract or geometric—distance, direction, something empty to be filled up. Place, on the other hand, is what space becomes when people imbue it with meaning. Dr. Thomas Gieryn, professor of Sociology at Indiana University, describes the difference between these terms beautifully. He writes:

“Places are endlessly made, not just when the powerful pursue their ambition through brick and mortar, not just when design professionals give form to function, but also when ordinary people extract from continuous and abstract space a bounded, identified, meaningful, named, and significant place. A place is remarkable, and what makes it so is an unwindable spiral of material form and interpretative understandings or experiences.”1

These “ordinary people”—the pedestrians, the viewers, the cultural critics—who play little part in physically constructing their landscape, have as much a role in shaping place as those who visually enact change to their urban environments.

So place and space are important, but so, obviously, are signs because signs are a necessary component in changing empty, abstract space into place. We live in a world that’s governed by signs: they tell us that we’re not walking into the men’s room by mistake; they tell us what we’re eating when we go to a buffet; and they tell us how to get where we’re going. But signs can also be thought of in a more general sense as any thing that represents another thing. The study of signs as elements of communication is called semiotics. It’s the study of how signs transmit or communicate meaning. And signs can be lots of different things: words, images, clothing—all of these things communicate something about the thing that they represent.

Any transmission of meaning in any given culture depends on the collective acceptance of codes within that culture. For example, if you think about the word “table” in English, there’s nothing inherent in the form of that word that means that thing—it’s just an arbitrary pairing of sounds and syllables that we agree means a piece of furniture with a flat surface supported by legs. This idea of language as an arbitrary collection of signs becomes more apparent when you think about other languages. In Spanish, the word for table is “mesa” and again, there is nothing inherent in that grouping of sounds that means that thing. People in Spanish speaking cultures have to collectively agree in order for it to make sense when someone speaks about a “mesa.”

But there are always subsets of people who agree that a sign represents something that the general public may not necessarily agree with. For a more concrete example, think about Boston’s Citgo sign. For most people, when they see a Citgo sign, they assume that there will be a Citgo gas station beneath it—but not us Bostonians! To us, the Citgo sign that perches high above Kenmore Square represents Boston itself, or Fenway Park, or the Red Sox, or even more abstractly, a certain pride in our hometown. And the Citgo sign is a designated landmark, not just because it’s a cool sign (and it is) but because we, as a collective group of Bostonians, have agreed that it means something more than gasoline.

So signs are complicated things. And Barry McGee knows that and he explores these complications in a lot of his work. For example, look at his facsimile of a dumpster with the words “R. Fong” spelled out across the front of it. In addition to these words (a name, perhaps?) there are also some amorphous gray shapes that indicate that the dumpster had been vandalized with graffiti tags that have since been buffed out or covered. These buffs imply that someone—someone with authority—came by and covered the graffiti because they found it offensive. Perhaps this graffiti was offensive because it used foul language, but more likely it was offensive because it challenges R. Fong’s ownership of that dumpster. But what makes us assume, first of all that R. Fong is a name, and second of all that he (or she!) is the owner of the dumpster? What is it about the lettering of R. Fong versus the lettering used in the graffiti tags that makes us, as a collective group, assume something about property rights?

But it’s clear that we do differentiate between those two types of lettering and that difference presents a challenge about what’s allowed and what’s not allowed in public space.

A common defense given by graffiti writers about their work is that they live in a world that’s consumed with advertisements everywhere you look. These graffiti writers claim that they were never asked how they feel about this bombardment of advertising and that they have just as much right to fill up public space with their own words and images as corporate entities do. What this comes down to is a power struggle about who gets to control public space. And who gets to control public space are people with money who have the intention to make more money.

This idea that the people who have money get to control space is not a new or a profound one, but I think we do have a tendency to think that the way things are now have always been that way and this is not true. The rise of capitalism that led to the proliferation of signs and advertising as we know it now had its start in the 18th century. Before that, before cities were planned to be these organized, rational spaces of commerce, when they just sprung up as commerce spread and new shops opened, a city like London, for example, had to be tamed.

So here comes the history lesson: Before the 18th century, most signs were for taverns and inns because the commercial shop hadn’t really come into being yet—people still went to the fair or the market to buy their goods. Also at this time, most people were illiterate so most of the signs that they would see every day were pictorial. These signs depicted images that most people agreed conveyed a certain idea or value about the place that it represented. For example, a lot of travelers at that time were pilgrims on religious retreats and they would know that an inn with a sign of the angel would be a good, Christian place for them to spend the night. Or if a Royalist were roaming the streets of London during the English Civil Wars of the 17th century, they would know that if they entered a tavern with a sign of a crown above it, they were more likely leave with their head intact.

The image above shows some common signs for inns and taverns around 1660-1675. But in the 18th century, things started to change pretty drastically with the spread of colonialism and the rise of the Industrial Revolution. As more products began to be produced in factories and imported from colonized lands, more and more shops began opening in London. And as more and more shops opened, more and more signs were needed. As competition started to grow, shopowners would opt for bigger and bigger (and thus heavier) projecting signs, some of which reached clear across the street, obstructing the already narrow lanes. Several times, these heavy projecting signs fell and injured or even killed innocent passersby.

Before the street naming and numbering system that we know today was implemented in the last decades of the 18th century, these pictorial signs literally mapped the city—they were the way that people got around, gave directions, and addressed mail. People would say things like “Meet me at the Sign of the Cock” and that would mean meet me at the tavern that has a sign with a rooster on it. Mail was addressed to “John Smith, at the Sign of the Bells” or even “John Smith, two doors down from the Sign of the Bells.” Mary Elliot, proprietor of a milliner’s (or hatmaker’s) shop in London advertises her business as being located “at the Wheat Sheaf and Star, opposite the pavement of St. Clement’s Church in the Strand.”

People were clued into the code of these pictorial signs and they would know that they could get their shoes cobbled at the sign of the shoe or a new pair of gloves at a sign that depicted a hand. But these signs were not always so straight-forward. Like Mary Elliot’s hat shop located at the Wheat Sheaf and Star, sometimes the sign that hung above the shop made very little logical sense.

You may have heard of some old English taverns with names like The Whale and Crow or The Shovel and Boot. These names came about as a result of shops going out of business and new ones moving in. Since these commercial signs were the main mode of navigation through the city, the new shopowners would sometimes opt to keep the sign of their predecessors so that people would know where they were located. But in order to differentiate themselves from the previous business, they often added their own symbol to the old sign, resulting in a kind of hodgepodge of unlikely pairings.

This kind of thing really frustrated people at the time and they would write into their local newspapers complaining about the lack of order that these signs represented. It was like the signs themselves were the reason for the disorder and confusion of city life. Joseph Addison, founder and editor of the wildly popular daily newspaper, The Spectator, wrote a humorous, yet pointed editorial about this phenomenon of mismatched signs in a 1711 edition of the paper. He wrote that he wished he had the authority to:

“forbid that Creatures of jarring and incongruous Natures should be joined together in the same sign […] The Fox and Goose may be supposed to have met, but what has the Fox and the Seven Stars to do together? and when did the Sheep and Dolphin ever meet, except upon a Sign-Post?”2

While this commentary is certainly amusing, it also speaks to the frustration of the city dweller in trying to decipher a landscape punctuated by seeming nonsense.

Though the tradition of adding a new symbol to an existing sign was prevalent, sometimes new shopowners decided not to add anything new to the existing sign and the public would just have to learn to accept that their new tailor did business under the Sign of the Roasted Pig. And sometimes, after a few businesses had already come and gone from a particular location, the public learned that the Sign of the Wheat Sheaf and Star now housed their local hatmaker. This kind of thing also frustrated people—they wanted the signs to correspond to the merchandise or services offered in the shop that they hung above.

We can understand this frustration today as well. We get frustrated even when we see a sign that says there’s milk on sale and when we go in the milk is already sold out. But what if we went in and it was a shoe store? This non-correspondence of signs to merchandise is another thing that Barry McGee explores in his work and he seems to enjoy exploiting our expectations.

Several years ago McGee collaborated with Stephen Powers and Todd James on an installation called Street Market. 3 The installation consisted of a kind of replication of a city street, complete with storefronts, graffiti, and even some pictorial signs à la the 18th century.

But the installation wasn’t intended to convey a city street as you would experience it in a real city, in part because the signs did not all correspond to the wares that they advertised.The lettering on the shops advertise for tube socks, VCRs, DVDs and some other more esoteric acronyms like DFW and THR.

But when you look into the windows of the shops, none of this advertised merchandise is inside (well, at least there are no VCRs, DVDs, or tube socks). Instead, the Lydia Fong “shop” looks more like a living room, with portraits on the wall and a coffee table and chairs. There are more price tags on the inside (if we assume that the numbers 1.99 necessarily equal money) but what they’re advertising for is pretty unclear. In this way, the artists are really messing with semiotics. What the heck are THR and DFW? What are these numbers referencing?

We can accept that these acronyms and numbers are maybe open to interpretation, maybe completely meaningless, maybe just esoteric. We can accept this range of possibilities because Street Market is a work of art in a gallery and placement matters in making sense of signs. Where something happens changes our perception of what is happening.

Think about the placement of graffiti—when it’s on the street, it’s illegal and when it’s in the gallery, it’s celebrated. But what about when graffiti is on the street but it’s not illegal? Does that confuse things?

Perhaps if you’re the kind of person that’s offended by graffiti, you might have sighed and rolled your eyes at the new, giant piece of vandalism on the Mass Turnpike near Fenway Park that popped up right around the time of the Barry McGee opening at the ICA in April. But what you might not know is that the new graffiti is actually part of the ICA’s Barry McGee exhibit.

If you are the kind of person that’s offended by graffiti, does this news change your view on these particular pieces of graffiti? Does it cease to be graffiti anymore?

It’s easy to write graffiti off when we see it in a place like the Mass Pike or along train tracks—places where we expect to see it. We just assume that it was done illegally and we make whatever judgment we’re going to make about it. But if a function of graffiti is to critique the onslaught of marketing that permeates our city streets, how do these pieces function now? Despite our personal view on the subject, when graffiti is associated with a museum, it no longer functions in the way we expect it to.

This idea that we should expect a sign (in both the literal and the more general sense) to function in a logical, rational way really started to take hold in the 18th century and it resulted in a major shift in the mode of navigation through the city streets. Besides the frustration of signs not corresponding to people’s expectations of them, in the mid 1700s, signs, as I mentioned, were also literally falling down and killing people. So not only were they seen as figuratively dangerous because they came to represent the disorder of the city, they were literally dangerous as well.

In 1762, the city of London issued an ordinance to remove all the projecting signs from the city streets and replace them with signs that were affixed to the front of the buildings. As this ordinance happened at a time when literacy was drastically increasing, most of the replacement signs featured words instead of or in addition to pictures.

Also around this same time, the government began implementing the street naming and numbering system that we know today. By removing the pictorial signs from the street and replacing them with names and numbers, what was really happening was an organization of the city space that allowed for businesses to exchange without having to rely on the pictorial signs to map them. With the numbering system, 1 Main Street is 1 Main Street, whether it’s a church or a tavern or a brothel. And in this way, 1 Main Street becomes more of a concept than an actual place—it becomes an empty space on a map that’s only thepotential for a church or a tavern or a brothel.

So what really happened with the implementation of the numbering system was a removal of place from space. It made the city more like an empty space where people and businesses can come and not have to leave any trace when they go. There’s no need to be clued into the semiology of the shop signs anymore—no need to say “meet me at the Sign of the Cock”—you can just say meet me at 1 Main Street.

This idea of place being removed from space is even more pronounced these days when we all have GPS in our cars and on our phones. There’s no need to even look at street signs anymore, nevermind shop signs—we just follow the blip on our screen and take a right when the GPS lady tells us to take a right.

Though this idea of enacting a rational, organized city space had its start in the 18th century, it really hit a high point in the last decades of the 20th century with the invention of vinyl technology for signage. Before the 1960s or so, all signs were made by hand, whether they were painted or carved or neon—somebody made them. The advent of vinyl technology in the early 1980s ushered in an era of quick, cheap, and easily replaceable signs that led to a homogenous and sterile urban landscape. In this way, vinyl signage can be seen as another incarnation of the numbering system of the 18th century, removingplace from space by making businesses more easily exchangeable and taking the human being out of the equation—a practice that is never a good idea for trying to retain a sense of place.

There are always forces working to separate place from space because the more exchangeable or generic a space is, the more potential it has to make money. But there are also always forces working to return place to space, working to imbue space with meaning and extract meaning from it. As Thomas Gieryn says, “places are endlessly made.”

I think this idea of returning place to space is a big part of the work that Barry McGee does in his art. So much of his work speaks to the urban experience of living in a place that isn’t always pretty or clean but is very human. Because like it or not, graffiti, and homeless people, and the grit of the city are part of what make a city a place. His attention to detail forces us to look around and understand that the dejected, the voiceless, the ugly, in addition to the funny and cute and colorful—all of these things make our cities home and they all deserve the attention of the ordinary person walking through the city and interpreting the meanings of its many signs.

(post republished from the bestdressedsigns blog)

———————

If I opened a pub it would be called the Pigeon and the Pancake.

(Pedigree prep)

(Pedigree prep)

See you next Thursday(7-9pm) in the gallery for this exciting event! Be sure to sneak a glance at Pedigree afterwards.

All that glitters is not gold.♥