(The Stolen Kiss, Jean-Honore Fragonard)

One time in college I was zoning-out in the dimly lit art history classroom amidst napping undergrads and filling out one of my countless “artist / date / movement / significance” flashcards. When all of a sudden my ears perked up—

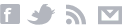

My prudish teacher began spouting off about trysts! debauchery! sex! infidelity! and immoral behavior!

Shelve the triptychs, let’s do this!

She was referring to Rococo, a movement which developed during the Late Baroque(18th century) period in France when artists gave up their symmetry and became increasingly ornate, floral, and playful.

Rococo first developed in the decorative arts and interior design and was often associated with the excesses of Louis XV’s reign. “Rococo rooms were designed as total works of art with elegant and ornate furniture, small sculptures, ornamental mirrors, and tapestry complementing architecture, reliefs, and wall paintings.”(via Wikipedia)

The use of delicate complex forms and intricate patterns spread among French artists and engraved publications and was readily received in Catholic parts of Germany and Austria where the movement merged with lively German Baroque traditions. Because the style was always thought of as “French taste”, Rococo was not as well received in Great Britain yet its influence was felt in the areas of silverwork, porcelain and silks.

William Hogarth helped develop a theoretical foundation for Rococo beauty. Though not intentionally referencing the movement, he argued in his Analysis of Beauty that the undulating lines and S-curves prominent in Rococo were the basis for grace and beauty in art or nature (unlike the straight line or the circle in Classicism).

The beginning of the end for Rococo came in the early 1760s as figures like Voltaire and Jacques-François Blondel(prominent French architect) began to voice their criticism of the superficiality and degeneracy of the art. Blondel condemned the “ridiculous jumble of shells, dragons, reeds, palm-trees and plants” in contemporary interiors and the style began to fall out of fash…

…ion.

Oh, right.

“Though Rococo originated in the purely decorative arts, the style showed clearly in painting. These painters used delicate colors and curving forms, decorating their canvases with cherubs and myths of love. Portraiture was also popular among Rococo painters. Some works show a sort of naughtiness or impurity in the behavior of their subjects, showing the historical trend of departing away from the Baroque’s church/state orientation. Landscapes were pastoral and often depicted the leisurely outings of aristocratic couples.”

Jean-Honore Fragonard was ALL over this.

(Blindman’s Bluff, Jean-Honore Fragonard)

During the 18th century, art and literature depicted courtship with encoded gestures and rituals because the society they reflected also used them. Everything people did or said had a meaning behind it, and often it was not the obvious one.

Many Rococo artists, including Fragonard, used symbols in their work. New symbols were developed for art, revolving around love and mythology. Statues of Venus, Cupid, and Psyche represented different aspects of love and were usually painted in the background to mirror the actions and sentiments of couples in the foreground.

Flower gardens are symbols of blossoming love, while a floral crown is a symbol of sexual consummation or commitment. A woman’s shoeless foot or parted skirts mean that she is unchaste; the same thing may be said about a man without a hat. The presence of a cat represents promiscuity while the dog is a symbol of fidelity. The presence of a letter often indicates letters of love.

The Rococo movement enabled Fragonard and others to express themselves in a new way and cover subject matter that was a bit more selacious than the landscapes, still lives, and pious family scenes depicted in earlier works from this time. Sex sells.

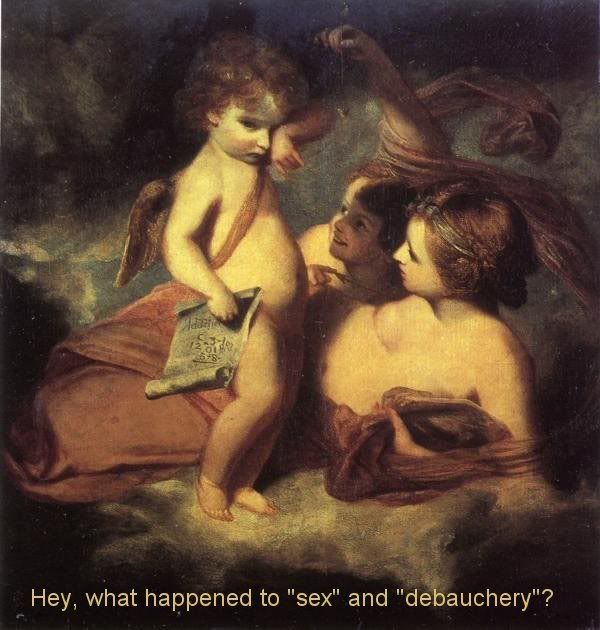

(The Meeting, Jean-Honore Fragonard)

One of Fragonard’s more famous pieces, The Meeting is exemplary of an idealized aristocratic view of young love. This representation of love may be seen in the iconography of the painting which depicts two lovers meeting in a garden(which was a common setting for such trysts) below a statue of Venus and Cupid. By presenting a fantasy of love for the upper classes Fragonard was also building on the tradition of idealization seen in French art set by previous artists such as Claude Lorraine and Antoine Watteau.

The glamorization of love seen in The Meeting comes about through its formal composition, which gives the painting a warm, feminine quality. But there are questions surrounding the couple’s expressions, were they unexpectedly interrupted? Are they looking to the left because they are concerned they will be caught? Scandy!

Fragonard exploits the sense of drama and heightened excitement which permeates The Meeting in order to portray the exuberance of new love. One must remember that in 18th-century France among the nobility marriages routinely were of convenience, with both men and women often having extramarital love interests. This cultural zeitgeist of decadent living among the aristocracy caused the commissioning of paintings with whimsical natures to flourish during the Rococo, and Fragonard had visited similar frivolous erotic subject matters in previous works such as The Swing from 1767.

(The Swing, Jean-Honore Fragonard)

The Swing depicts a lady in a pink dress seated on a swing on which she floats through the air, her skirts billowing, while a hidden gentleman observes from a thicket of bushes; the landscape setting emphasizes a bluish, smoky atmosphere, foaming clouds, and foliage sparkling with flickering light. Pictures like The Swing brought Fragonard harsh criticism from Denis Diderot, a leading philosopher of the Enlightenment. Diderot charged the artist with frivolity and admonished him to have “a little more self-respect.” Set in a rich landscape, an aristocratic young woman, identified as the patron’s mistress, is being pushed on a swing by a bishop. Facing her, lying on the ground, is her lover; she kicks up her leg, lifting her skirts and tossing him her shoe, symbolizing the sexual favors she bestowed upon him. (via enlightenment-revolution)

(Autumn Pastoral, Francois Boucher)

While this post focuses primarily on the work of Fragonard, artists such as François Boucher and the aforementioned Antoine Watteau were covering the subject of impropriety as well. Boucher is known for his Odalisque series of paintings which sparked controversy over “prostituting his wife”(in the dark-haired version) and spotlighting the extramarital affairs of the King(in the blonde version). After harsh criticism primarily from Diderot(what a buzzkill!), Boucher fell out of favor and his reputation was tarnished during the last of his creative years.

(Pilgrimage on the Isle of Cythera, Antoine Watteau)

The aforementioned Antoine Watteau(who is probably the most well known of the Rococo painters) created his famous “fête galante“(defined:an amorous celebration or party enjoyed by the elite aristocracy of France during the reign of Louis XV) piece Pilgrimage on the Isle of Cythera which captured the frivolity and sensuousness most often associated with this style of painting.

(Self Portrait in a Straw Hat, Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun

I would be remiss if I did not mention that during this time Élisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun was a force to be reckoned with as a prominent female artist and is recognized as the most famous female painter of the eighteenth century.

Unfortunately, while Élisabeth was highly skilled, she primarily focused on aristocrat portraiture which doesn’t make for an engaging FLUX. post/Maury Povich show, but feel free to check out additional information on her here.

(The Love Letter..with a few adjustments, Jean-Honore Fragonard)

Feel free to send me love letters. Or flat-out stalk me.

(For more information on Rococo and the primary sources of my research, please visit new world encyclopedia, lover of wisdom, various artist Wikipedia pages, and enlightenment-revolution. Wouldn’t be able to write this if it wasn’t for source material!)♥