Last night I was working on a John James Audubon writeup for today’s FLUX.

When I opened my browser this morning, I noticed the following on Google’s homepage:

(!) Didn’t realize his birthday was today (April 26, 1785)!

Coincidence. Conspiracy.

“Audobon was a walking contradiction. Meticulously accurate in his science, he told tall tales and even outright lies. His name is synonymous with American conservation but he killed thousands of birds, he was jailed for bankruptcy but dined with Earls, Dukes, and Presidents. He was a faithful husband and father who abandoned his wife and family for years at a time, he was a failed merchant and a fabulous success.”

Since I got a bit derailed with my iTunes giftcard and used the remaining balance on Pretty Pet Salon and Bejeweled, the Phantom Itunes Project is squashed. BUT, the yet-to-be-named Netflix project is in full force.

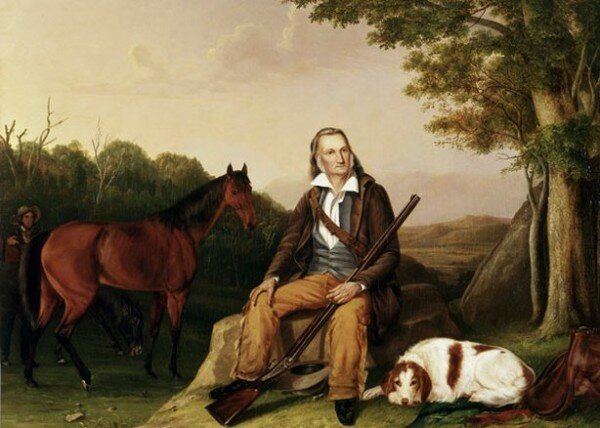

I recently watched John James Audubon: Drawn From Nature and thought it was an interesting look inside the life of this charismatic and prolific illustrator. Most famous for cataloging the birds of North America, this documentary sheds light on his painstaking process, his personal and private life, and his rise to fame.

You can find out most of the nitty gritty about Audubon’s life from Wikipedia , but I wanted to highlight a few areas I found particularly interesting in Drawn From Nature

- He was the son of a French ship captain, his wife was a french chambermaid in his house, and his mother died when he was 6 months old. Because this situation wouldn’t be looked at kindly by 19th century society of the time he made up stories about his past, hinting that he might be the lost heir to the throne of france, or born in Louisiana, and he would change his story constantly and always recreated himself.

- He loved collecting curiosities from nature, he kept pickled snakes and amphibians in jars, pelts, beehives, natural history, eggs, nests, stuffed birds.

- Before audobon pictures of birds were lifeless, sitting on twigs, and the proportions and articulations were all wrong, but even Audobon fell into this issue early on saying “My pencil gave birth to a family of cripples, so maimed were most of them that they resembled the mangled corpses on a field of battle”

- The reason his paintings were so accurate and detailed was because he would kill birds in order to study them. He would pose them the way he wanted on a grid, pin them down, outlined them with a compass, sketched and colored them accordingly so it looked as though they were being observed in their natural habitat.

- Any day he didn’t shoot 100 birds was a “day wasted”. He used a shotgun because the small pieces of ‘shot’ wouldn’t destroy the feathers of the specimen.

- One plate which clearly distinguishes a contrast between Audubon’s earlier and later styles is his rendering of the Northern Goshawk.

The lower birds which were cut and pasted to sheet, look stiff, and don’t appear to be moving while the upper bird’s feet are spread apart, wings outstretched, beak open and looks alive.

- Audubon developed a method of drawing that involved employing a variety of media to achieve a certain effect including pastel ink chalk, oil goache, watercolor pencil, and would make his own brushes sometimes using a single hair

- All of Audobon’s plates are illustrated in painstaking detail through a multi-step process. For example very single barbule and feather of the Carolina Parakeets are outlined in iridescent graphite on their plate, amounting to thousands of feathers and hours of work.

- As his style evolved his birds were no longer floating in space and he employed assistants to help paint scenes.

- Audobon was a bit of a showman, and would write up elaborate stories about the birds in nature. When he ran out of interesting stories he would write his friends asking for their own anecdotes to use.

- Audubon had to file for bankruptcy, the bank took everything from his home, his furniture, curtains, pianos, and paintings. But nobody wanted his paintings, so he was able to keep them. But his wife lost everything.

- In 1871, Audobon’s widow Lucy, desperate for cash, sold 435 copper plates to be melted down as scrap. They were thrown into the fire until a 14 year old boy, son of the factory foreman, was able to save 79 original plates from The Birds of America.

On the surface, the subject matter seems a bit dull. You get it. It’s a guy who draws birds. But if you watch the documentary, you’ll see his life was packed with scandal, drama, and it portrays him as a real person struggling to overcome difficult issues and faults that often times a quick historical blip in your Survey of Art course seems to soften out.

If you have Netflix and a spare 55 minutes, it’s definitely a good watch.

“If I were jealous I would have a bitter time of it, for every bird is my rival” – Lucy Audubon

♥